Understanding the brain with the help of artificial intelligence

How does consciousness arise? Researchers suspect that the answer to this question lies in the connections between neurons. Unfortunately, however, little is known about the wiring of the brain. This is due also to a problem of time: tracking down connections in collected data would require man-hours amounting to many lifetimes, as no computer has been able to identify the neural cell contacts reliably enough up to now. Scientists from the Max Planck Institute of Neurobiology in Martinsried plan to change this with the help of artificial intelligence. They have trained several artificial neural networks and thereby enabled the vastly accelerated reconstruction of neural circuits.

Neurons need company. Individually, these cells can achieve little, however when they join forces neurons form a powerful network which controls our behaviour, among other things. As part of this process, the cells exchange information via their contact points, the synapses. Information about which neurons are connected to each other when and where is crucial to our understanding of basic brain functions and superordinate processes like learning, memory, consciousness and disorders of the nervous system. Researchers suspect that the key to all of this lies in the wiring of the approximately 100 billion cells in the human brain.

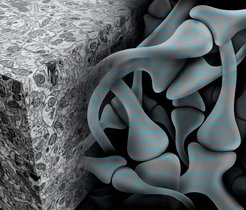

To be able to use this key, the connectome, that is every single neuron in the brain with its thousands of contacts and partner cells, must be mapped. Only a few years ago, the prospect of achieving this seemed unattainable. However, the scientists in the Electrons – Photons – Neurons Department of the Max Planck Institute of Neurobiology refuse to be deterred by the notion that something seems “unattainable”. Hence, over the past few years, they have developed and improved staining and microscopy methods which can be used to transform brain tissue samples into high-resolution, three-dimensional electron microscope images. Their latest microscope, which is being used by the Department as a prototype, scans the surface of a sample with 91 electron beams in parallel before exposing the next sample level. Compared to the previous model, this increases the data acquisition rate by a factor of over 50. As a result an entire mouse brain could be mapped in just a few years rather than decades.

Although it is now possible to decompose a piece of brain tissue into billions of pixels, the analysis of these electron microscope images takes many years. This is due to the fact that the standard computer algorithms are often too inaccurate to reliably trace the neurons’ wafer-thin projections over long distances and to identify the synapses. For this reason, people still have to spend hours in front of computer screens identifying the synapses in the piles of images generated by the electron microscope.

However the Max Planck scientists led by Jörgen Kornfeld have now overcome this obstacle with the help of artificial neural networks. These algorithms can learn from examples and experience and make generalizations based on this knowledge